About the Author

Dr. Brenda Bautsch Dickhoner is the Common Sense Institute Mike A. Leprino Free Enterprise Fellow. Brenda has spent over a decade working in education policy at the national and state level. For CSI, she has authored research on education finance, charter schools and COVID-19 learning loss. Previously, at the Colorado Department of Education, she developed and implemented policies to ensure all students have access to a high-quality education. Brenda earned a Ph.D. in Public Policy at the University of Colorado Denver School of Public Affairs and studied political science as an undergraduate at Duke University.

About Common Sense Institute

Common Sense Institute is a non-partisan research organization dedicated to the protection and promotion of Colorado’s economy. CSI is at the forefront of important discussions concerning the future of free enterprise in Colorado and aims to have an impact on the issues that matter most to Coloradans. CSI’s mission is to examine the fiscal impacts of policies, initiatives, and proposed laws so that Coloradans are educated and informed on issues impacting their lives. CSI employs rigorous research techniques and dynamic modeling to evaluate the potential impact of these measures on the Colorado economy and individual opportunity. Common Sense Institute was founded in 2010 originally as Common Sense Policy Roundtable. CSI’s founders were a concerned group of business and community leaders who observed that divisive partisanship was overwhelming policymaking and believed that sound economic analysis could help Coloradans make fact-based and common sense decisions.

About the Colorado Business Roundtable

The Colorado Business Roundtable (COBRT) is a public policy organization comprised of executives from some of the state’s largest employers working to strengthen Colorado’s economic vitality. COBRT engages with elected leaders, business and nonprofit leaders, and other strategic allies to improve the business climate in our state by unapologetically amplifying the voice of business in all four corners of Colorado.

Introduction

Research has long documented the positive effect immigrants have on the U.S. economy.[i] Through immigration, businesses are able to fill critical skill gaps, reduce hiring shortages, and produce more goods and services. This allows businesses to grow and create more jobs for U.S.-born workers, increasing overall employment levels.[ii]

Researchers have found that immigrants augment the existing workforce, debunking the myth that immigrants compete with native workers for jobs.[iii] Moreover, immigration has been found to increase the real wages of U.S.-born workers. One study on the effects of immigration found that immigrants in California spurred wage gains of up to 6.7% for the state’s native workers who had at least a high school degree.[iv]

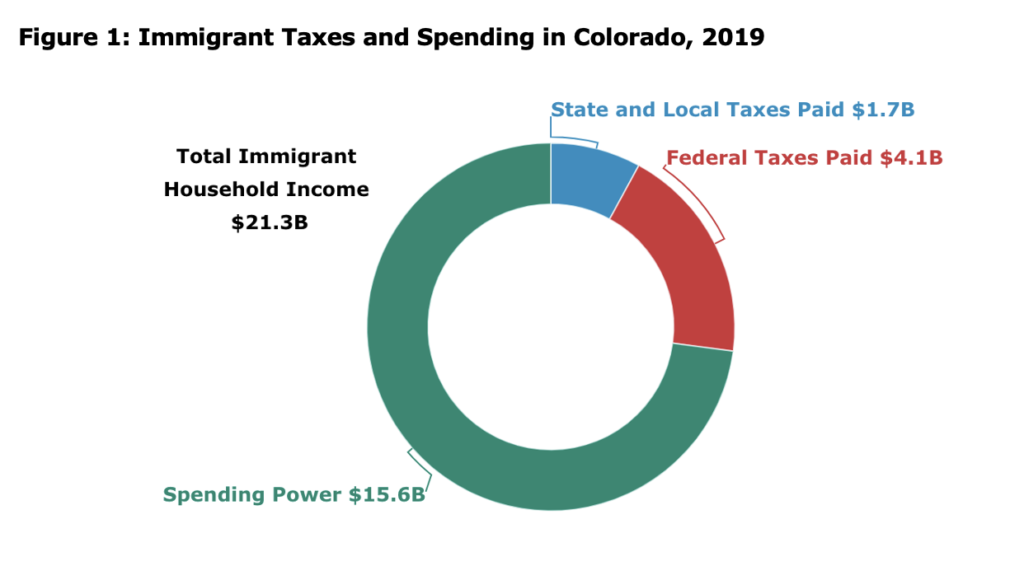

In addition, immigrants bolster economic growth through their tax contributions, spending on goods and services, and participation in the housing market.[v] In 2019, Colorado immigrants paid $5.8 billion in local, state and federal taxes.[vi] After paying taxes, immigrant households in Colorado retained over $15.6 billion in income in 2019, equating to significant spending power. Further, nearly 130,000 immigrants in Colorado are homeowners, contributing to over $56 billion in housing wealth.[vii]

The Business Roundtable summarizes these effects of immigration, writing: “Numerous analyses have shown that the immigrant workforce boosts GDP; increases employment, wages and income; reduces government deficits; supports the housing market; and promotes entrepreneurship and innovation that keep our economy dynamic.”[viii]

Immigration in Colorado

Statewide Economic Impact

In 2019, Colorado was home to 537,334 immigrants, who comprised 9.3% of the state’s population.[ix] Immigrants make up a disproportionately larger share of the workforce because they are more likely to be of working age. About 83 percent of non-native born workers are between ages 16 and 64, compared to 64 percent of the US-born population in Colorado.[x] These immigrants positively impact the state’s economy through their tax contributions and spending. Figure 1 displays data on income, taxes and spending power for immigrants in Colorado.

Source: New American Economy, 2019, Available at: https://www.newamericaneconomy.org/locations/colorado/

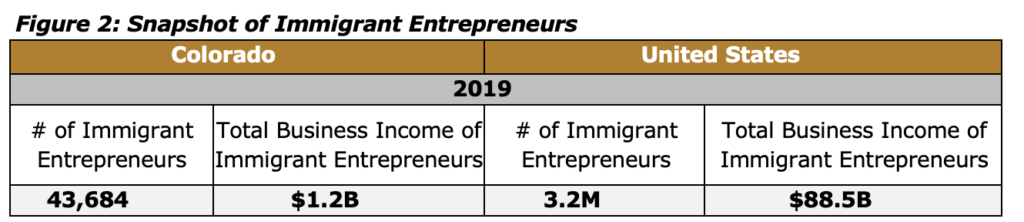

Entrepreneurship

America is built on the entrepreneurial spirit of immigrants. To this day, immigrants continue to spur new innovations and technologies and take industries into new directions. Immigrant-led innovations increase capital productivity and benefit U.S.-born workers through growth in jobs and wages.[xi] Immigrants start new businesses at twice the rate of U.S.-born individuals.[xii] According to data compiled by the New American Economy, “in 2016, 40.2 percent of Fortune 500 firms had at least one founder who either immigrated to the United States or was the child of immigrants.”[xiii] These immigrant-founded companies employ millions of Americans and contribute billions of dollars to the U.S. GDP.

Source: New American Economy, 2019. Available at: https://www.newamericaneconomy.org/locations/colorado/ and https://www.newamericaneconomy.org/locations/national/

COVID-19 & Immigrants

Essential Workers

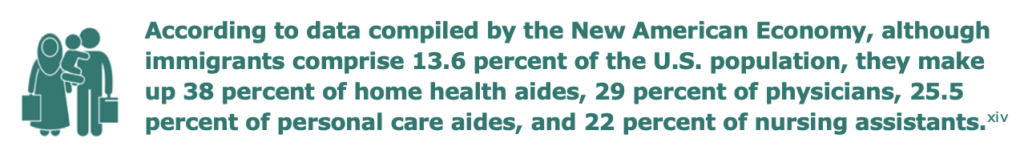

In addition to comprising a high share of the country’s entrepreneurs, immigrants also make up a disproportionately high share of many essential jobs.

In Colorado, while immigrants make up 9.3 percent of the state’s population, they comprise 15.8 percent of health aids.[xv] These key health care positions have become more critical during the COVID-19 pandemic, and immigrants are serving alongside native-born health care workers putting themselves at high risk of exposure in caring for others. Immigrants are also disproportionately more likely to be filling other essential jobs such as janitors and cleaners, childcare workers, food preparation workers, cooks, and taxi and truck drivers.[xvi]

In Colorado, while immigrants make up 9.3 percent of the state’s population, they comprise 15.8 percent of health aids.[xv] These key health care positions have become more critical during the COVID-19 pandemic, and immigrants are serving alongside native-born health care workers putting themselves at high risk of exposure in caring for others. Immigrants are also disproportionately more likely to be filling other essential jobs such as janitors and cleaners, childcare workers, food preparation workers, cooks, and taxi and truck drivers.[xvi]

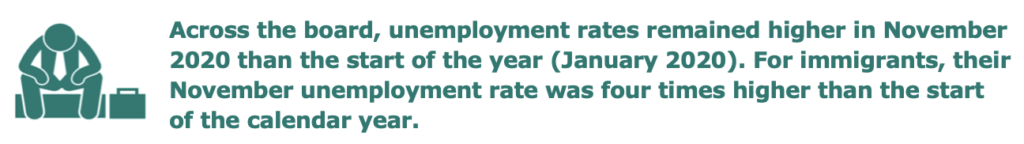

Unemployment

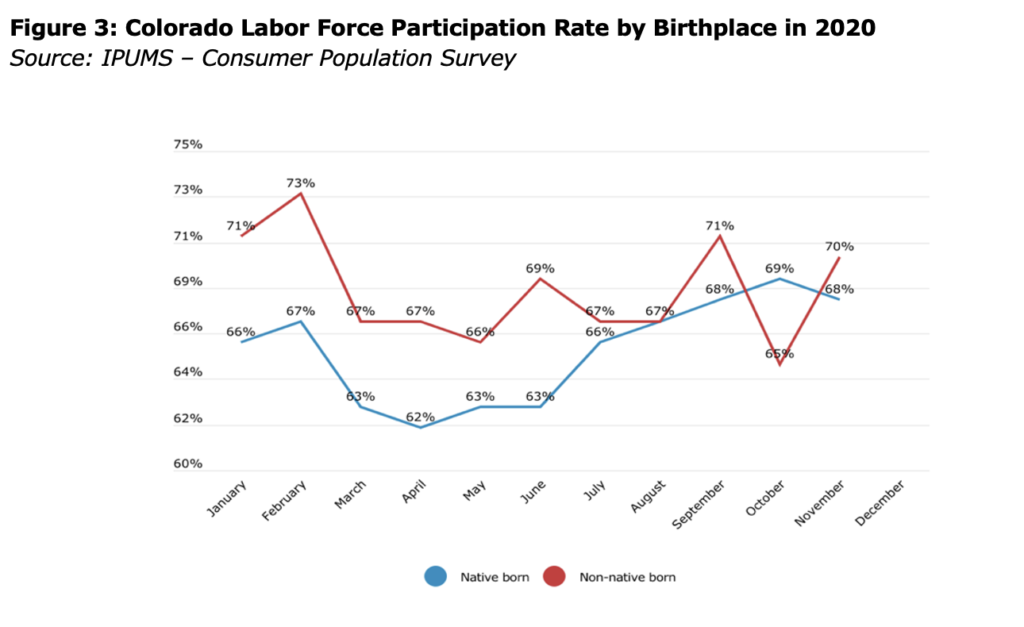

While immigrants serve an outsized role in many essential fields right now, they have not been immune to the layoffs that have affected wide swaths of the population. Immigrants saw a particularly large spike in unemployment rates as the pandemic closed businesses in spring 2020 (see Figure 3). The unemployment rate for non-native born workers increased from 4.2 percent in March 2020 to 21.7 percent in April 2020. The unemployment rate for native workers also increased in April 2020, going up to 9.8 percent from 4.2 percent in March. The large spike in unemployment for immigrants receded fairly quickly and unemployment rates hovered around 6 percent to 7.7 percent in late summer to fall.

Supporting all working adults, including immigrants, in returning to the labor force will be a critical part of overall economic recovery.

Source: IPUMS – Consumer Population Survey

Source: IPUMS – Consumer Population Survey

Economic Impact on Counties

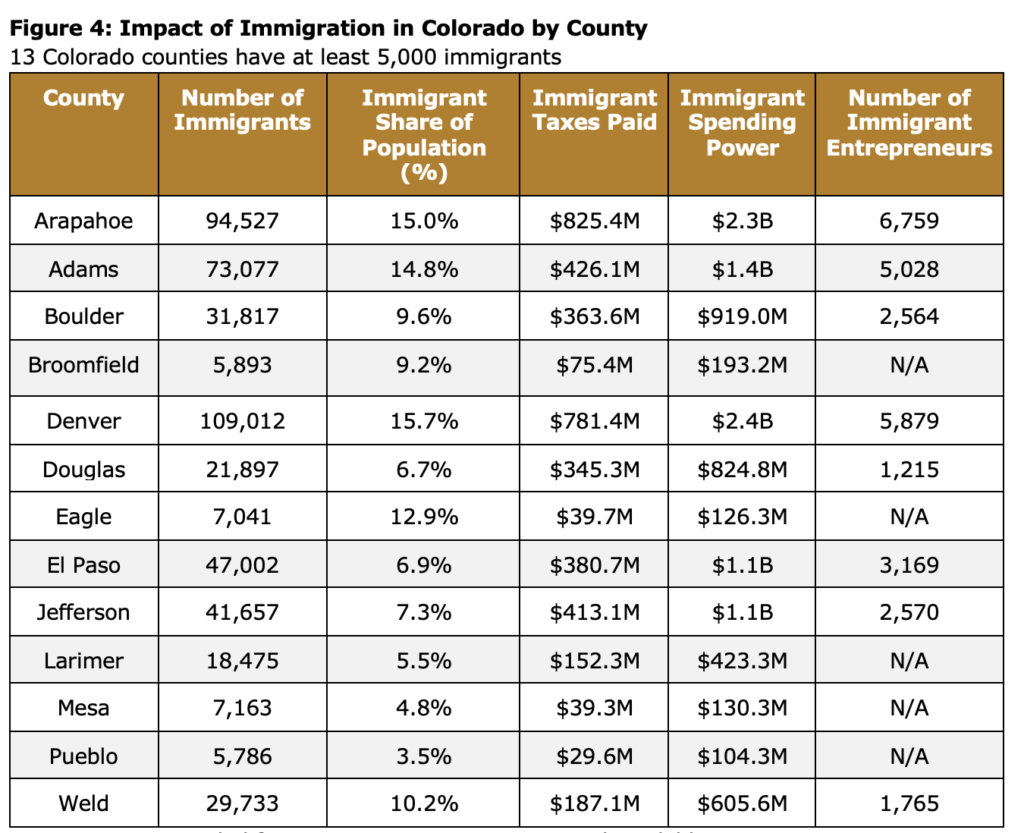

The 13 counties listed in Figure 4 each have more than 5,000 immigrant residents, and combined they are home to 91 percent of all immigrants in the state. Nearly 30,000 of the immigrants living in these 13 counties are entrepreneurs.

In 2019, while Denver had both the largest total number (109,012) and share of immigrants (15.7 percent) in the state, Arapahoe County had the largest number of immigrant entrepreneurs (6,759). Relative to total county population, Adams County also stands out as having a high share of immigrant entrepreneurs, just behind Arapahoe County and ahead of Denver and Boulder.

Source: Data compiled from New American Economy and available at: https://data.newamericaneconomy.org/map-the-impact/

Visas

U.S. employers rely on visas to bring in foreign workers to fill key workforce shortages. Visa programs require applicants to demonstrate that they cannot fill the position with a U.S. worker. Thus, the high number of requests for visas by U.S. companies reflects a real need for foreign labor. Further, research has found benefits from visa programs on the U.S. economy as a whole. One study, for example, found that “as high-skilled H-1B immigrant admissions increase, so does the rate of American inventions.”[xvii] Other data shows that visas create more jobs for US-born workers.

Additionally, given the importance of immigrant entrepreneurship, many business leaders suggest there should be a specific visa for immigrants who want to obtain permanent residence in the U.S. to both start and grow a new business.[xix]

Colorado Visa Data

In 2020, Colorado was ranked third in the nation for receiving certified positions through the H-2B visa program, following Texas and Florida.[xx] Under the H-2B visa program, U.S. employers can hire foreign workers to perform nonagricultural labor or services on a temporary basis. In 2020, 46.1 percent of H-2B visas nationwide were issued for groundskeeping and landscaping positions.[xxi]

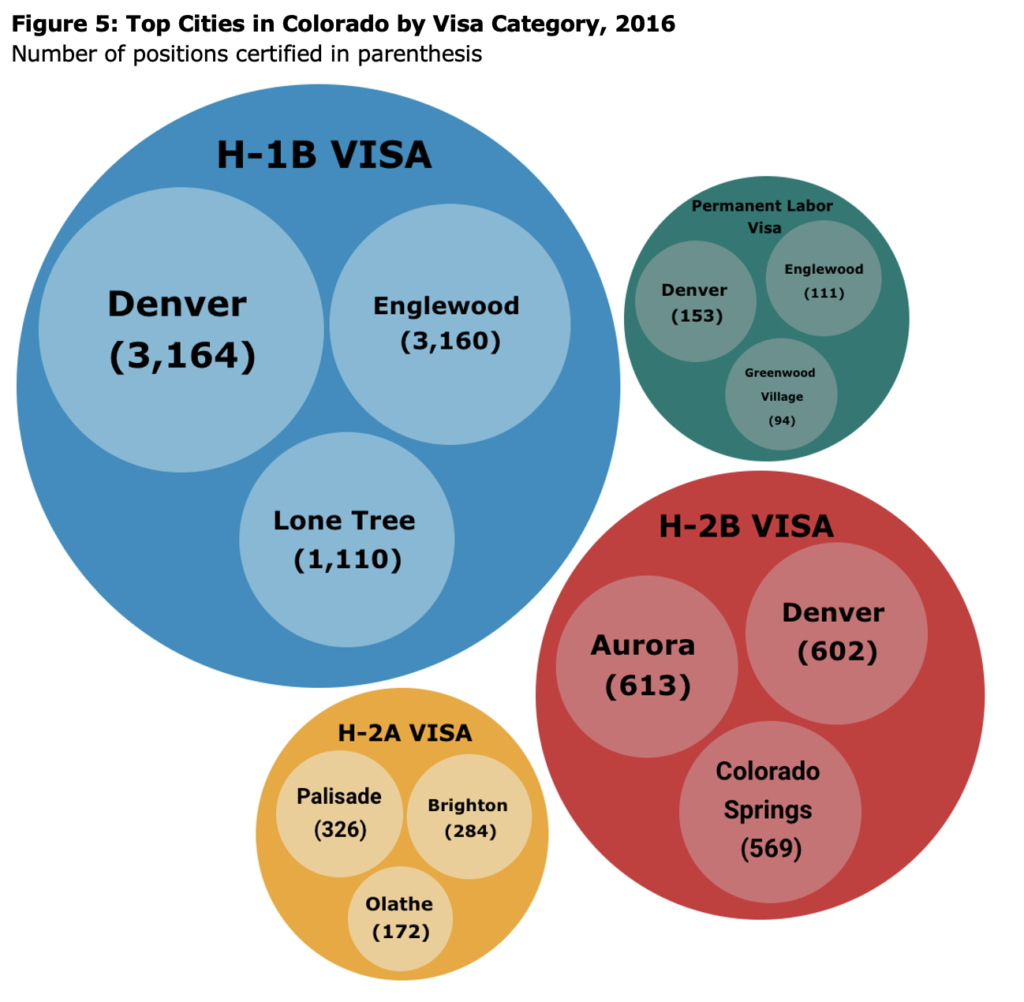

Other visa programs include the H-1B visa for high-skilled, specialty occupations, H-2A visas for temporary agricultural positions, and permanent visas for employers to hire foreign workers on a long-term basis. In 2016, Colorado employers received certification from the U.S. Department of Labor for 22,215 positions across a wide variety of occupations and geographies. This included:

● 13,103 positions for workers on H-1B visas,

● 2,058 positions for H-2A workers,

● 6,179 positions for H-2B visas, and

● 875 positions for workers with a permanent visa.[xxii]

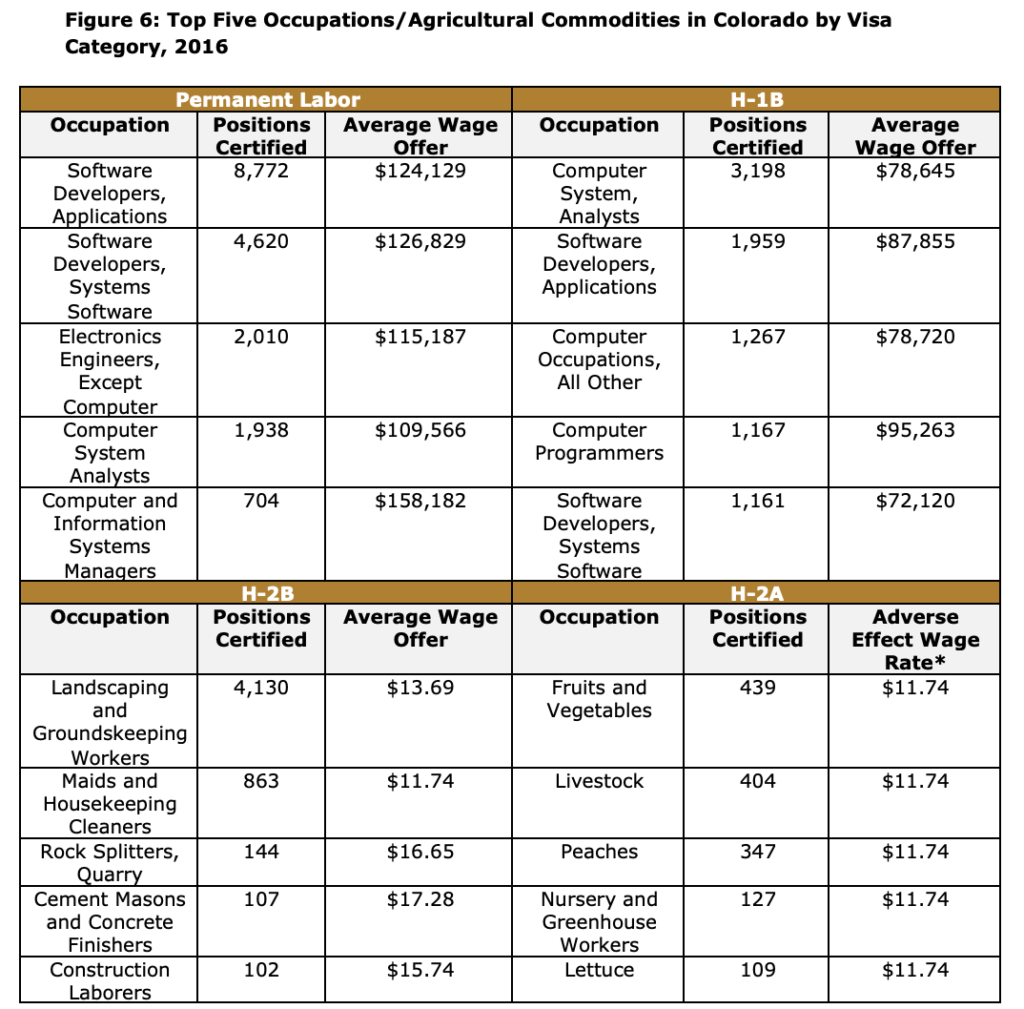

Top cities and occupations for the different visa programs in Colorado are displayed in Figures 5 and 6.

Source: U.S. Department of Labor, Office of Foreign Labor Certification, Annual Report 2016, p. 57. Available at: https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ETA/oflc/pdfs/OFLC_Annual_Report_FY2016.pdf

*Adverse Effect Wage Rate is effectively the federal minimum wage for certain agricultural workers.

Source: U.S. Department of Labor, Office of Foreign Labor Certification, Annual Report 2016, p. 57. Available at: https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ETA/oflc/pdfs/OFLC_Annual_Report_FY2016.pdf

Conclusion

Research shows that immigrants strengthen the U.S. economy through their entrepreneurship, tax contributions, spending power and by filling critical workforce gaps. U.S.-born workers see more job opportunities and higher wages as a result of immigration. Currently, there is a complex array of laws, visa categories and regulations that often overlap and create inefficiencies. Establishing a coherent and fair immigration system for foreign workers who wish to legally contribute to the US economy is a priority of business leaders and many policymakers. Already the policy landscape is beginning to shift under a new presidential administration. As regulatory changes around immigration and foreign workers continue to occur, the following organizations serve as resources for finding up-to-date information:

● Colorado Business Roundtable: https://www.cobrt.com/

● US Business Roundtable: https://www.businessroundtable.org/

● New American Economy: https://www.newamericaneconomy.org/

Research Notes

[i] See, for example, Furchgott-Roth, D. (2014). “Does Immigration Increase Economic

Growth?”; Hanson, G. (2012). “Immigration and Economic Growth”; Boubtane, E., J. Dumont and C. Rault. (2015). “Immigration and Economic Growth in the OECD Economies, 1986–2006”; Anderson, S. (2011). “Answering the Critics to Immigration Reform.”

[ii] Business Roundtable. (2017). Economic Effects of Immigration Policies. Retrieved from:

https://www.remi.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/569-Economic-Effects-of-Immigration-Policies.pdf

[iii] See, for example, Furchtgott-Roth, D. (2014); Zavodny, M. and T. Jacoby. (2013). “Filling

the Gap: Less-Skilled Immigration in a Changing Economy”; Peri, G. and C. Sparber. (2010). “Highly Educated Immigrants and Native Occupational Choice”; Peri, G. and C. Sparber. (2010). “Assessing Inherent Model Bias: An Application to Native Displacement in Response to Migration”; Hunt, J. (2012). “The Impact of Immigration on the Educational Attainment of Natives.”

[iv] Peri, G. (2007). “Immigrants’ Complementarities and Native Wages: Evidence from

California.” National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w12956/w12956.pdf

[v] Business Roundtable, 2017.

[vi] New American Economy. (2019). “Immigrants and the Economy: Colorado.” Retrieved from: https://www.newamericaneconomy.org/locations/colorado/

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Business Roundtable, 2017, p. 2.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Business Roundtable, 2017.

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] New American Economy. (2016). “Reason for Reform: Entrepreneurship.” p.2 Retrieved

from: http://www.newamericaneconomy.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Entrepreneur.pdf

[xiv] New American Economy. (2020). “Working Immigrants at Risk of COVID-19.” Retrieved

from: https://data.newamericaneconomy.org/en/immigrant-workers-at-risk-coronavirus/

[xv] New American Economy, 2019.

[xvi] Ibid.

[xvii] Business Roundtable, 2017, p. 4.

[xviii] New American Economy. (2016). P 19. The Contributions of New Americans in Colorado.

Retrieved from: http://research.newamericaneconomy.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/nae-co-report.pdf

[xix] Ibid.

[xx] U.S. Department of Labor. (2020). ”Office of Foreign Labor Certification: H-2B Temporary

Non-Agricultural Program – Selected Statistics, Fiscal Year (FY) 2020 EOY.” Retrieved from: https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ETA/oflc/pdfs/H-2B_Selected_Statistics_FY2020.pdf

[xxi] Ibid.

[xxii] U.S. Department of Labor. (2016). Office of Foreign Labor Certification: Annual Report

2016, p. 57. Retrieved from: https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ETA/oflc/pdfs/OFLC_Annual_Report_FY2016.pdf